- April 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

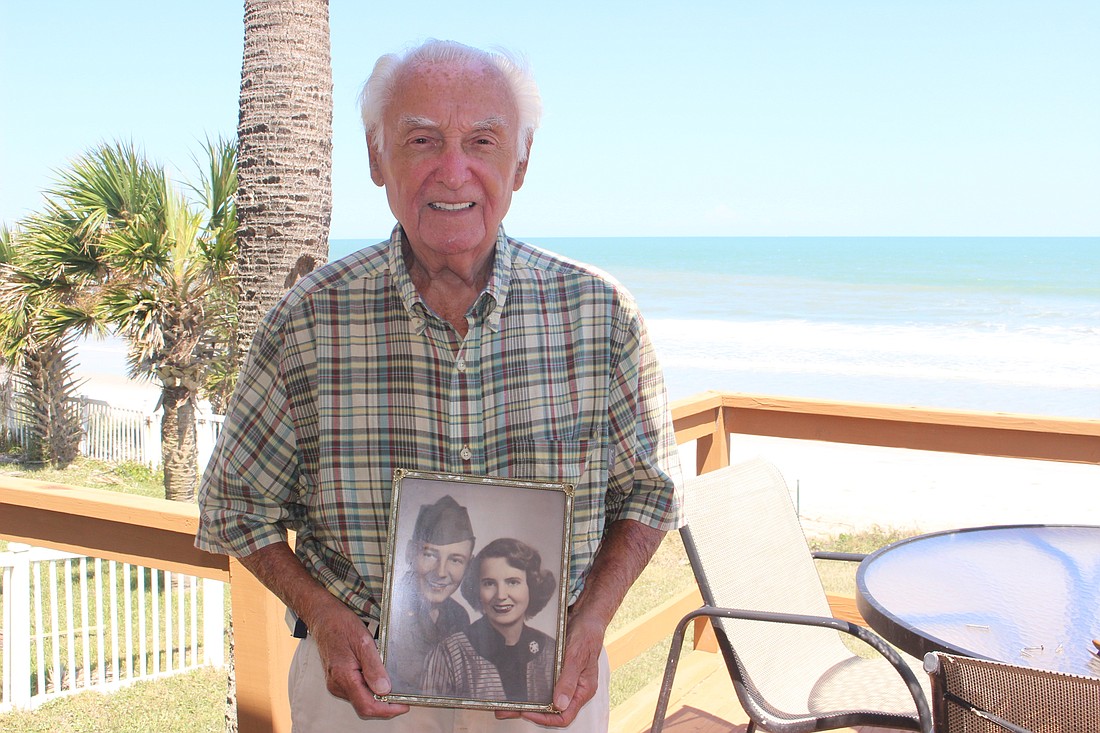

As sure as the waves that flow into the sands of his backyard, Russ Acker’s beachfront home is a haven of memories.

His daughter’s portrait hangs over a mantle in the living room, not far from her two treasured pianos — one upright and one grand— that used to sing at her fingertips. His son’s photo isn’t far, guarding the doorway between the living room and the breakfast nook, and there are touches of Acker’s wife throughout. The flowered white sectional sofa is solid proof of that.

This is the house Acker, 88, has lived in for 28 years, and for the past two, it’s the house where he has lived through two hurricanes.

“Whenever the good Lord wants me, he’ll take me,” Acker said.

His son, James, helped him put up plywood to cover all the windows in his house, including the large ones in the back facing the beach. Without fear of the hurricane or the corresponding storm surge, Acker hunkered down in his home through it all. When the power went out, he navigated the house by candlelight after dark.

Except shutting off power, Hurricane Irma did not impact his home aside from a little water he quickly mopped away. Acker’s power came back on at 8:20 p.m. Wednesday, Sept. 13.

And while power is a definite necessity, there is one activity he didn’t need it for—his favorite.

Acker loves walking on the beach.

Acker met his wife, Julie, while they were studying education at Florida Southern College in Lakeland. They knew they wanted to get married, but Acker’s father had only promised to put him through college if he was single, so they had to wait a little bit. Julie graduated a year before Acker, but in 1951, 10 days after Acker’s graduation, the pair finally wed.

The Ackers moved to Julie’s hometown of Coleman, Florida, a town that even today houses fewer than 1,000 people. They worked as schoolteachers, making $5,000 a year together.

After just one year of marriage, Acker was drafted into the army to go fight in the Korean War. He wasn’t sure if he would come back or not, but he did. While he was overseas, he wrote a letter to his father in Madison, New Jersey, asking if he would hire him in his brokerage firm in New York.

“He said, 'I’ll pay you $50 a week,'” Acker said. “'Boy,' I said, 'I don’t know what we’ll make about that.'”

They would only make about $200 a month.

“Julie said, ‘Whatever it is, we’ll live on it,’” Acker said. “She could stretch a dollar bill til it squeaked.”

The Ackers moved to New Jersey after he came back from the war and worked with his father for six years, moving on to another firm in New York afterward where he spent 20 years. Somewhere along the way, his son James and daughter Debbie were born.

On May 1, 1980, Acker opened up his own investment and trading firm. In December, Julie was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and had to have a hysterectomy.

Acker said he spent a year going back and forth from the hospital to his business until she went into remission.

The Ackers then made the decision to move back to Florida, and they opened a firm in Daytona Beach. In 1986, they moved into a riverfront home on Dresden Circle in Ormond Beach, where they had opened another branch of Acker-Wolman Security Corp.

But a few years later, almost every time Acker would get home from work, Julie and Debbie were gone. He figured they were out fishing or something similar. They’d pull in to the driveway shortly after him, and told him they were over at the ocean.

“That went on for about a month,” Acker said. “I said, 'Something’s going on. What’s the deal?'”

His wife and daughter told him they had seen a house the liked for sale. It was on the beach.

“I said, 'Forget it, I can’t afford the ocean,'” Acker said. “'You’re crazy'”

They worked on him for another month, and sure enough, Acker ended up buying the house—the same one he currently lives in.

There’s a painting of the beach hanging in his living room. His daughter Debbie painted it.

Debbie had cystic fibrosis, and having their own firm, Julie was able to take care of her.

“Your spirit kind of moves you. It tells you: ‘You should do this’. And that’s what I do."

Russ Acker, Ormond Beach resident

“She really had a tough life, but a wonderful life,” Acker said.

Debbie spent a year in an intensive care unit in North Carolina awaiting a double-lung transplant. On Thanksgiving Day in 1992, a young woman from Tampa died. Her lungs were intact.

While Debbie laid on the operating table, that young woman’s lungs were making her way over to her. Unfortunately, Debbie’s heart gave out during the operation.

Debbie was a 34-year-old biomedical engineer with a doctorate from Duke University.

Her death strengthened the Ackers.

“We said, ‘Well, she’s in a much better place,’” Acker said. “She’s up in heaven. She wouldn’t have had a good quality of life.”

Every morning and every afternoon, Acker walks on the beach and he greets everyone he sees.

“I’ve met so many nice people on the beach,” Acker said.

That’s where he met Nashville residents Leeanne Lane and her mother Charlene. Lane was on vacation in Ormond Beach celebrating her mother’s birthday, and they also love to walk on the beach. It’s not unusual for them to meet people on their trips, but Acker stood out to them.

Lane said it was an immediate connection.

“He just is such a kind man, you know?” Lane said. “Super sweet and we loved his energy and the fact that his age doesn’t keep him from being adventurous.”

Lane was only in town for a week, but shortly after meeting, Acker offered to drive them to St. Augustine for lunch. They spent the day together talking, and before they left for Nashville, they had coffee and donuts at Acker’s house.

“We literally could have sat there all day and night and just chatted,” Lane said.

They loved how giving Acker is, and that combined with Acker’s age, was one of the things that set him apart from others.

“He just wanted to give his time and his energy to whatever and whoever would be willing to take it,” Lane said.

During the short time they spent together, Acker, Lane and her mother traded life stories with each other, and found common ground despite living thousands of miles apart.

Lane is a carrier for cystic fibrosis.

“It was just the little things like that,” Lane said. “The more we talked, the more things we had in common and we just loved about each other.”

When they heard Hurricane Irma was going to impact Florida, they were worried about him—sometimes calling him twice a day before the storm to make sure he was okay.

But Acker wasn’t worried.

“I don’t think about dying at all—not one iota,” Acker said.

If it was his time to go, then it was his time, he added. The fact that his wife isn’t with him anymore is also a factor of his choice to stay.

“If Julie was alive, we would’ve left the house,” he said, laughing. “She was chicken.”

Julie died on July 22, 2016. Acker had been working on getting an elevator installed in their home at the time, and she never got to use it.

“After Julie died, this house was awful quiet,” Acker said.

She’s buried in a crypt in the Grace Lutheran Church along with their daughter Debbie.

“That’s where I’m going to go, too,” Acker said. “My name is on the slab. The only thing it doesn’t have is the date.”

Since being retired in 2006, the beach is where he meets the majority of people he talks to. He’s met schoolteachers and vacationers, and made lifelong friendships. He’s even driven to other states to comfort friends he’s met strolling on the sands.

He wasn’t going to let any hurricane change that.

“Your spirit kind of moves you,” Acker said. “It tells you: ‘You should do this.' And that’s what I do, and I love it. I just love it. I feel so happy and so fortunate every day that I live—that I can be at a place where I can meet people on the beach.”